1.2.2 Democratic governance and a human rights framework

The central responsibility to protect human rights rests with the States which have broad obligations under international human rights law, namely to respect, protect and fulfil human rights. In order for these obligations to be met at the national level, States are required to take “all appropriate steps”, including legislative and institutional steps, to ensure rights are realised at the State level. Establishing NHRIs is an important way of doing this because NHRIs link international human rights to the domestic or national human rights framework.

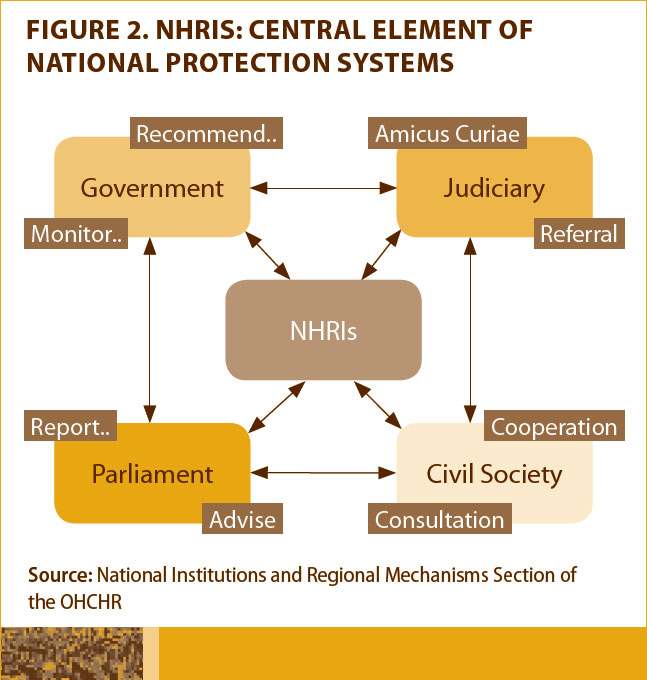

NHRIs that comply with the Paris Principles are cornerstones of national human rights protection, and can be a force for making international human rights obligations a national reality. NHRIs are therefore central elements of national human rights protection systems. They work hand in hand with other parts of the State and with social actors: these include the executive, an independent judiciary, law enforcement agencies, effective and representative legislative bodies, strong and dynamic civil society organisations, a free press, and education systems containing human rights programmes at all levels.

NHRIs can provide a central role in building a culture of human rights, while reinforcing the rule of law. Operating within a national framework, NHRIs typically draw on rights from several sources: first, their mandate is typically derived from a combination of a national constitution and legislation. Operating together, the constitution and enabling legislation will guarantee the NHRI’s existence and independence, and authorise its actions. While NHRIs are not, of course, at the centre of a country’s governance system, seeing the inter-relationships can help to place NHRIs in context with other actors in government as figure 2 does:

NHRIs also draw their authority and responsibilities from regional and international human rights obligations arising from treaties, covenants and other instruments. NHRIs thus foster the link between international law and the national framework by encouraging the incorporation of international human rights norms into the domestic framework of rights.

Third, the development of guidelines and principles, sometimes called “soft law”, provides interpretative guidance for understanding NHRIs and their work.

To summarise, the mandate of NHRIs – what they can and should do – depends on three things:

- First, the constitution and NHRI’s enabling legislation, which form a legal basis and confer lawful authority to act.

- Second, international instruments that are ratified in the country have legal effect and are a principal source of human rights law (In some countries, ratified conventions or covenants are automatically part of the country’s law. In others, the country must take an extra step and enact legislation.).

- Third, there are various types of principles that aid in interpreting instruments or laws. There are specific guidelines or standards that apply to NHRIs and these are called the Paris Principles. Although the term is not universally accepted, such principles are sometimes called “soft law” because, while they are not binding, they do provide interpretive guidance and tend to have a normative effect.